Visit Armenia, it is beautiful

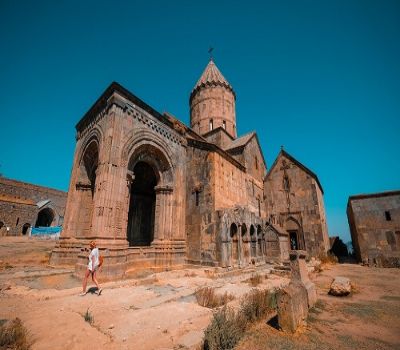

Armenia is a nation, and former Soviet republic, in the mountainous Caucasus region between Asia and Europe. Among the earliest Christian civilizations, it’s defined by religious sites including the Greco-Roman Temple of Garni and 4th-century Etchmiadzin Cathedral, headquarters of the Armenian Church. Khor Virap Monastery is a pilgrimage site near Mount Ararat, a dormant volcano just across the border in Turkey.

History of Armenia

The Armenians, an Indo-European people, first appear in history shortly after the end of the 7th century BCE. Driving some of the ancient population to the east of Mount Ararat, where they were known to the Greeks as Alarodioi (“Araratians”; i.e., Urartians), the invaders imposed their leadership over regions which, although suffering much from Scythian and Cimmerian depredations, must still have retained elements of a high degree of civilization (e.g., walled towns, irrigation works, and arable fields) upon which the less-advanced newcomers might build.

The Hayk, as the Armenians name themselves (the term Armenian is probably the result of an Iranian or Greek confusion of them with the Aramaeans), were not able to achieve the power and independence of their predecessors and were first rapidly incorporated by Cyaxares into the Median empire and then annexed with Media by Cyrus II (the Great) to form part of the Achaemenian Empire of Persia (c. 550 BCE). The country is mentioned as Armina and Armaniya in the Bīsitūn inscription of Darius I (the Great; ruled 522–486 BCE) and, according to the 5th-century Greek historian Herodotus, formed part of the 13th satrapy (province) of Persia, the Alarodioi forming part of the 18th. Xenophon’s Anabasis, recounting the adventures of Greek mercenaries in Persia, describes the local government about 400 BCE as being in the hands of village headmen, part of whose tribute to the Persian king consisted of horses. Armenia continued to be governed by Persian or native satraps until its absorption into the Macedonian empire of Alexander the Great (331). After the empire was divided between Alexander’s generals, Armenian rulers paid tribute to the Seleucid kingdom (301), although in practice they wielded considerable autonomy.

The Artaxiads

After the defeat of the Seleucid king Antiochus III (the Great) by Rome at the Battle of Magnesia (winter 190–189 BCE), his two Armenian satraps, Artaxias (Artashes) and Zariadres (Zareh), established themselves, with Roman consent, as kings of Greater Armenia and Sophene, respectively, thus becoming the creators of an independent Armenia. Artaxias built his capital, Artashat (Artaxata), on the Aras River near modern Yerevan. The Greek geographer Strabo refers to the capital of Sophene as Carcathiocerta. An attempt to end the division of Armenia into an eastern and a western part was made about 165 BCE when the Artaxiad ruler sought to suppress his rival, but it was left to his descendant Tigranes II (the Great; 95–55 BCE) to establish, by his conquest of Sophene, a unity that was to last almost 500 years.

Under Tigranes, Armenia ascended to a pinnacle of power unique in its history and became, albeit briefly, the strongest state in the Roman east. Extensive territories were taken from the kingdom of Parthia in Iran, which was compelled to sign a treaty of alliance. Iberia (Georgia), Albania, and Atropatene had already accepted Tigranes’ suzerainty when the Syrians, tired of anarchy, offered him their crown (83 BCE). Tigranes penetrated as far south as Ptolemais (modern ʿAkko, Israel).

Although Armenian culture at the time of Tigranes was Iranian, as it had been and as it was fundamentally to remain for many centuries, Hellenic scholars and actors found a welcome at the Armenian court. The Armenian empire lasted until Tigranes became involved in the struggle between his father-in-law, Mithradates VI Eupator of Pontus, and Rome. The Roman general Lucius Licinius Lucullus captured Tigranocerta, Tigranes’ new capital, in 69 BCE. He failed to reach Artashat, but in 66 BCE the legions of Pompey, aided by one of Tigranes’ sons, succeeded, compelling the king to renounce Syria and other conquests in the south and to become an ally of Rome. Armenia became a buffer state, and often a battlefield, between Rome and Parthia. Maneuvering between larger neighbours, the Armenians gained a reputation for deviousness; the Roman historian Tacitus called them an ambigua gens (“ambiguous people”).

The Arsacids

Both Rome and Parthia strove to establish their own candidates on the Armenian throne until a lasting measure of equilibrium was secured by the treaty of Rhandeia, concluded in 63 CE between the Roman general Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo and Tiridates (Trdat), brother of the Parthian king Vologeses I. Under this treaty a son of the Parthian Arsacid dynasty, the first being Tiridates, would occupy the throne of Armenia but as a Roman vassal. A dispute with Parthia led to Armenia’s annexation by the Roman emperor Trajan in 115 or 116, but his successor, Hadrian, withdrew the frontier of the Roman Empire to the Euphrates. After the Roman emperor Caracalla’s capture of King Vagharshak and his attempt to annex the country in 216, his successor, Macrinus, recognized Vagharshak’s son Tiridates II (Khosrow the Great in Armenian sources) as king of Armenia (217).

Tiridates II’s resistance to the Sāsānid dynasty after the fall of the Arsacid dynasty in Persia (224) ended in his assassination by their agent Anak the Parthian (c. 238) and in the conquest of Armenia by Shāpūr I, who placed his vassal Artavazd on the throne (252). Under Diocletian, the Persians were forced to relinquish Armenia, and Tiridates III, the son of Tiridates II, was restored to the throne under Roman protection (c. 287). His reign determined the course of much of Armenia’s subsequent history, and his conversion by St. Gregory the Illuminator and the adoption of Christianity as the state religion (c. 314) created a permanent gulf between Armenia and Persia. The Armenian patriarchate became one of the surest stays of the Arsacid monarchy and the guardian of national unity after its fall. The chiefs of Armenian clans, called nakharars, held great power in Armenia, limiting and threatening the influence of the king.

The dissatisfaction of the nakharars with Arshak II led to the division of Armenia into two sections, Byzantine Armenia and Persarmenia (c. 390). The former, comprising about one-fifth of Armenia, was rapidly absorbed into the Byzantine state, to which the Armenians came to contribute many emperors and generals. Persarmenia continued to be ruled by an Arsacid in Dvin, the capital after the reign of Khosrow II (330–339), until the deposition of Artashes IV and his replacement by a Persian marzpān (governor) at the request of the nakharars (428). Although the Armenian nobles had thus destroyed their country’s sovereignty, a sense of national unity was furthered by the development of an Armenian alphabet and a national Christian literature; culturally, if not politically, the 5th century was a golden age. (See Armenian literature.)

The marzpāns

The Persians were not as successful as the Byzantines in their efforts to assimilate the strongly individualistic Armenian people. The misguided attempt of the Persian Sāsānian king Yazdegerd II to impose the Zoroastrian religion upon his Armenian subjects led to war in 451. The Armenian commander St. Vardan Mamikonian and his companions were slain at the Battle of Avarayr (June 2?, 451), but the Persians renounced their plans to convert Armenia by force and deposed their marzpān Vasak of Siuniq, the archtraitor of Armenian tradition.

The revolt of 481–484, led by Vahan Mamikonian, Vardan’s nephew, secured religious and political freedom for Armenia in return for military aid to Persia, and with the appointment of Vahan as marzpān the Armenians were again largely the arbiters of their own affairs. Their independence was further asserted in 554, when the second Council of Dvin rejected the dyophysite formula of the Council of Chalcedon (451), a decisive step that cut them off from the West as surely as they were already ideologically severed from the East. (According to the dyophysite formula, Christ, the Son of God, consists of two natures, “without confusion, without change, without separation, without division.”)

In 536 the Byzantine emperor Justinian I reorganized Byzantine Armenia into four provinces, and, by suppressing the power of the Armenian nobles and by transferring population, he completed the work of Hellenizing the country. In 591 its territory was extended eastward by the emperor Maurice as the price of helping the Sāsānian king Khosrow II regain the Persian throne. After transporting many Armenians to Thrace, Maurice (according to the Armenian historian Sebeos) advised the Persian king to follow his example and to send “this perverse and unruly nation, which stirs up trouble between us,” to fight on his eastern front. During the war between the emperor Phocas and Khosrow, the Persians occupied Byzantine Armenia and appointed a series of marzpāns, only to be ousted by the emperor Heraclius in 623. In 628, after the fall of Khosrow, the Persians appointed an Armenian noble, Varaztirotz Bagratuni, as governor. He quickly brought Armenia under Byzantine rule but was exiled for plotting against Heraclius (635).

People of Armenia

Armenians constitute nearly all of the country’s population; they speak Armenian, a distinct branch of the Indo-European language family. The remainder include Kurds, Russians, and small numbers of Ukrainians, Assyrians, and other groups. Most of Armenia’s Azerbaijani population fled or was expelled after the escalation of the conflict between the two countries. More than 3 million Armenians live abroad, including about 1.5 million in the states of the former Soviet Union and about 1 million in the United States.

The Armenians were converted to Christianity about 300 CE and have an ancient and rich liturgical and Christian literary tradition. Believing Armenians today belong mainly to the Armenian Apostolic (Orthodox) Church or the Armenian Catholic Church, in communion with Rome.

The Russian campaigns against the Persians and the Turks in the 18th and 19th centuries resulted in large emigrations of Armenians under Muslim rule to the Transcaucasian provinces of the Russian Empire and to Russia itself. Armenians settled in Yerevan, Tʿbilisi, Karabakh, Shemakha (now Şamaxı), Astrakhan, and Bessarabia. At the time of the massacres in Turkish Armenia in 1915, some Armenians found asylum in Russia. A number settled in the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh within the neighbouring Muslim country of Azerbaijan. Armenians now constitute about three-fourths of the population of Nagorno-Karabakh; since 1988 there have been violent interethnic disputes and sporadic warfare between Armenians and Azerbaijanis in and around the enclave.

The economic crisis of the 1990s caused substantial numbers of Armenians to emigrate. By the mid-1990s an estimated 750,000 Armenians—about one-fifth of the population—had left the country.

At present, Armenia’s birth rate is below the world’s average, and its death rate is higher than average. About one-fifth of the population is under age 15, and more than two-fifths is under age 30. Life expectancy, averaging 75 years of age, is about the global mean.

Cultural Life of Armenia

Cultural Life

Armenian written literature began in the 5th century AD, and monasteries became the principal centres of intellectual life. The earliest works were historical, such as Moses of Khoren’s History of Armenia. The masterpiece of classical Armenian is Eznik Koghbatsi’s Eghts aghandots (Refutation of the Sects). The first great Armenian poet (10th century) was St. Gregory Narekatzi, renowned for his mystical poems and hymns. During the 16th to 18th century, popular bards, or troubadours, called ashugh, arose; outstanding among them were Nahapet Kuchak and, especially, Aruthin Sayadian, called Sayat-Nova (d. 1795), whose love songs are still popular. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Hakob Paronian and Ervand Otian were notable satirical novelists, and Grigor Zohrab wrote realist short stories. Paronian was also a comic playwright, whose plays still entertain Armenian audiences. The most celebrated novelist was Hakob Meliq-Hakobian, called Raffi, and perhaps the best dramatist of recent times was Gabriel Sundukian (d. 1912).

The country boasts a State Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet, several drama theatres, theatres for children, orchestras, a national dance company, and the Yerevan film studios, which produce feature, documentary, and science films. The traditional folk arts, especially singing, dancing, and artistic crafts, are popular. The 20th-century Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian achieved worldwide renown.

The public libraries include the A.F. Myasnikyan State Public Library and the Matenadaran archives in Yerevan, which contain 10,000 Armenian manuscripts, the largest collection in the world. There are also a number of museums, including the State Historical Museum of Armenia.

Armenian science, like its culture, has its roots in antiquity, but research institutions are a 20th-century development. The Armenian Academy of Sciences is composed of a number of institutes engaged in research problems in natural and social sciences.

The radio broadcasting system has been operating since 1926, and the Yerevan television centre since 1956. Broadcasts and telecasts are conducted in Armenian, Russian, Azerbaijani, and Kurdish. Many newspapers and periodicals are published in Armenia, most of them in the Armenian language.

Unique Armenian Cuisine

Armenian food derives most of its magic from the great abundance, quality, and freshness of its locally sourced ingredients. Experiencing Armenia means trying all of the delicious meals it has to offer. Whether it’s in a modern restaurant, a fast food spot, or a traditional home cooked meal – Armenia has many flavors to satisfy your tastebuds.

Cuisine That Has Stood the Test of Time

Armenian cuisine has stood the test of time for two millennia and offers bountiful tables of mouthwatering dishes that are accompanied with intimate drinks and toasts. Here, you will enjoy an inexpensive full dinner at a respectable restaurant, a glass of wine or brandy, and local fruits and berries at the markets fresh from the orchard.

Armenia is a place where recipes are passed on from generation to generation and the signature of specialties become a treasured family secret. It is a place where chefs conjure in the kitchen by keeping to traditional recipes, interpreting or even boldly experimenting with old ones.