Ireland - A breath of fresh air

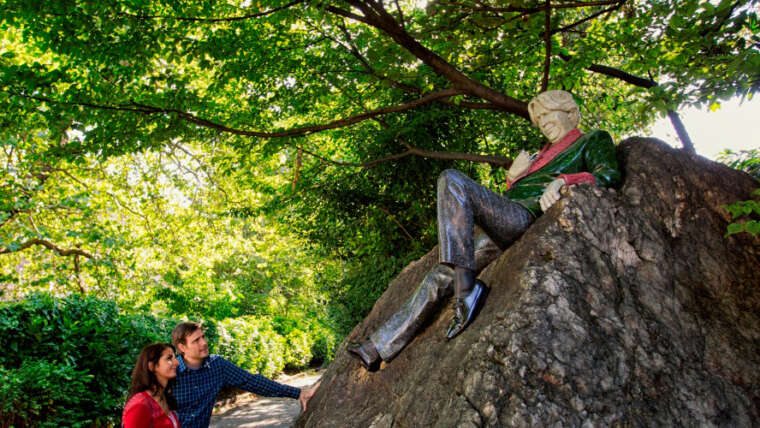

The Republic of Ireland occupies most of the island of Ireland, off the coast of England and Wales. Its capital, Dublin, is the birthplace of writers like Oscar Wilde, and home of Guinness beer. The 9th-century Book of Kells and other illustrated manuscripts are on show in Dublin’s Trinity College Library. Dubbed the “Emerald Isle” for its lush landscape, the country is dotted with castles like medieval Cahir Castle.

Enjoy Irish hospitality as you travel through Ireland’s iconic cities and charming villages, from Dublin and Galway to Cork and Killarney. Tour through the countryside of Ireland taking in the ancient castles and natural wonders, see the Cliffs of Moher and the Dingle Peninsula, venture to the Aran Islands, and kick back in a cosy pub to sample the Irish Whiskey and locally brewed Guinness.

History of Ireland

Ireland, lying to the west of Britain, has always been to some extent cut off by it from direct contact with other European countries, especially those from Sweden to the Rhine River. Readier access has been through France, Spain, and Portugal and even Norway and Iceland. Internally, the four ecclesiastical provinces into which Ireland was divided in the 12th century realistically denoted the main natural divisions of the country. Of these, the north had in the earliest times been culturally connected with Scotland, the east with Roman Britain and Wales, the south with Wales and France, and the southwest and west with France and Spain. In later times, despite political changes, these associations continued in greater or lesser degree.

The position of Ireland, geographically peripheral to western Europe, became “central” and thus potentially more important once Europe’s horizons expanded in the 15th and 16th centuries to include the New World. Paradoxically it was in the earlier period that Ireland won particular fame as a notable and respected centre of Christianity, scholarship, and the arts. After the Middle Ages, subjugation to Britain stultified—or the struggle for freedom absorbed—much of Ireland’s native energy. But its influence was always exercised as much through its emigrants as in its achievements as a nation. During the centuries of British occupation the successors of the great missionaries and scholars who had fostered Christianity and learning among the Germanic peoples of the European continent from the 7th to 9th century were those who formed a considerable element in the armies and clergy of Roman Catholic countries and had an incalculable influence on the later development of the United States. Throughout history innumerable people of Anglo-Irish origin or nurture have had a constant and profound influence, as statesmen or soldiers, on the history of both Ireland and Britain.

Early Ireland

The human occupation of Ireland did not begin until a late stage in the prehistory of Europe. It generally was held that the first arrivals to Ireland were Mesolithic hunter-fisher people, represented largely by flintwork found mainly in ancient beaches in the historic counties of Antrim, Down, Louth, and Dublin. These artifacts were named Larnian, after Larne, Northern Ireland, the site where they were first found; dates from 6000 BCE onward were assigned to them. Archaeological work since World War II, however, casts considerable doubt on the antiquity and affinities of the people who were responsible for the Larnian industry; association with Neolithic remains suggests that they should be considered not as a Mesolithic people but rather as groups contemporary with the Neolithic farmers. The Larnian could then be interpreted as a specialized aspect of contemporary Neolithic culture. Lake and riverside finds, especially along the River Bann, show a comparable tradition. A single carbon-14 date of 5725 ± 110 BCE from Toome Bay, north of Lough Neagh, for woodworking and flint has been cited in support of a Mesolithic phase in Ireland, but such a single date cannot be considered reliable.

Neolithic Period

The general pattern of carbon-14 date determinations suggests that the Neolithic Period (New Stone Age) in Ireland began about 3000 BCE. As in Britain, the most widespread evidence of early farming communities is long-barrow burial. The main Irish long-barrow series consists of megalithic tombs called court tombs because an oval or semicircular open space, or court, inset into the end of the long barrow precedes the burial chamber. There are more than 300 of these court tombs. They occur in the northern half of Ireland, and the distribution is bounded on the south by the lowlands of the central plain. Timber-built rectangular houses belonging to the court tomb builders have been discovered at Ballynagilly, County Tyrone, and at Ballyglass, County Mayo. The court tombs are intimately related to the British long-barrow series of the Severn-Cotswold and chalk regions and probably derive from more or less common prototypes in northwestern France.

In Ireland a second type of megalithic long barrow—the so-called portal tomb, of which there are more than 150 examples—developed from the court tomb. They spread across the court tomb area in the northern half of Ireland and extend into Leinster and Waterford and also to western Wales and Cornwall.

Another notable feature of the Irish Neolithic is the passage tomb. This megalithic tomb, unlike the long-barrow types, is set in a round mound, sited usually on a hilltop and grouped in cemeteries. The rich grave goods of these tombs include beads, pendants, and bone pins. Many of the stones of the tombs are elaborately decorated with engraved designs. The main axis of the distribution lies along a series of great cemeteries from the River Boyne to Sligo (Boyne and Loughcrew in County Meath, Carrowkeel and Carrowmore in County Sligo). Smaller groups and single tombs occur largely in the northern half of the country and in Leinster. A specialized group of later—indeed, advanced Bronze Age—date near Tramore, County Waterford, is quite similar to a large group on the Isles of Scilly and Cornwall. The great Irish passage tombs include some of the most magnificent megalithic tombs in all of Europe—for example, Newgrange and Knowth in Meath. While the passage tombs represent the arrival of the megalithic tradition in its fullest and most sophisticated form, the exact relation between the builders of these tombs and the more or less contemporary long-barrow builders is not clear. The passage tombs suggest rather more clearly integrated communities than do the long barrows.

To the final stage of the Neolithic probably belong the rich house sites of both rectangular and circular form at Lough Gur, County Limerick. The pottery shows a strong connection with the tradition of the long barrow (court tomb and portal tomb).

Bronze Age

Two great incursions establish the early Bronze Age in Ireland. One, represented by approximately 400 megalithic tombs of the wedge tomb variety, is associated with Beaker pottery. This group is dominant in the western half of the country. Similar tombs also associated with Beaker finds are common in the French region of Brittany, and the origin of the Irish series is clearly from this region. In Ireland the distribution indicates that these tomb builders sought well-drained grazing land, such as the Burren limestones in Clare, and also copper deposits, such as those on the Cork-Kerry coast and around the Silvermines area of Tipperary.

In contrast, in the eastern half of the country a people in the single-burial tradition dominate. Their burial modes and distinctive pottery, known as food vessels, have strong roots in the Beaker tradition that dominates in many areas of western Europe. They may have reached Ireland via Britain from the lowland areas around the Rhine or farther north.

Throughout the early Bronze Age Ireland had a flourishing metal industry, and bronze, copper, and gold objects were exported widely to Britain and the Continent. In the middle Bronze Age (about 1500 BCE) new influences brought urn burial into eastern Ireland. From about 1200 BCE elements of a late Bronze Age appear, and by about 800 BCE a great late Bronze Age industry was established. A considerable wealth of bronze and gold is present, an example of which is the great Clare gold hoard. Nordic connections have been noted in much of this metalwork.

Iron Age

The period of the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in Ireland is fraught with uncertainties. The problem of identifying archaeological remains with language grouping is notoriously difficult, but it seems likely that the principal Celtic arrivals occurred in the Iron Age. Irish sagas, which probably reflect the pagan Irish Iron Age, reveal conditions in many respects similar to the descriptions of the ancient Classical authors, such as Poseidonius and Julius Caesar. The Celts were an Indo-European group who are thought to have originated in the 2nd millennium BCE, probably in east-central Europe. They were among the earliest to develop an Iron Age culture, as has been found at Hallstatt, Austria (c. 700 BCE). Although there is little sign of Hallstatt-like culture in Ireland, the later La Tène culture (which may date in Ireland from 300 BCE or earlier) is represented in metalwork and some stone sculpture, mainly in the northern half of the country. Connections with northern England are apparent. Hill fort building seems also characteristic of the Iron Age.

People of Ireland

Although Ireland was invaded and colonized within historical times by Celts, Norsemen, Normans, English, and Scots, there are no corresponding ethnic distinctions. Ireland has always been known as a welcoming place, and diversity is not a phenomenon new to the country.

Ethnic groups, language, and religion

Ethnic and racial minorities make up about 12 percent of the population of Ireland—a proportion that doubled in the first decade of the 21st century. Immigration from the rest of Europe, Africa, and Asia has been significant since the last two decades of the 20th century. The key factors in increased immigration have been the more-open labour market provided by the European Union and the globalized nature of the contemporary Irish economy, both of which have attracted a wave of new residents. Today Poles constitute the largest minority population in Ireland. Although they are small in number, the nomadic Travellers (“Tinkers”) are an indigenous ethnic minority group—defined by their shared customs, traditions, and language—who have lived in Ireland for centuries.

The constitution provides that Irish be the first official language and English the second. All official documents are published in both Irish and English. The modern Irish language, which is very similar to Scottish Gaelic, was widely spoken up to the time of the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s and the subsequent emigrations. The use of Irish continued to decline even after 1922, when the language was introduced into schools; despite its decline, Irish never ceased to exert a strong influence on Irish consciousness. Although its use as a vernacular has decreased and is concentrated in several small Gaeltacht (i.e., Irish-speaking) areas, Irish is more widely read, spoken, and understood today than it had been during most of the 20th century. English is universally spoken. Compulsory Irish in schools has come under some criticism from the business sector, which would prefer to see students develop more-diverse language skills. While modern society might question the utility of the language, however, it remains an important element of the Irish identity.

The Celtic religion had a major influence on Ireland long before the adoption of Christianity in the 5th century. Its precise rituals and beliefs remain somewhat obscure, but the names of hundreds of Celtic gods have survived, and elements of the religion—particularly the cults of Mary (an echo of Danu, the Earth Mother goddess whom the Celts worshiped) and St. Brigid (one of Ireland’s patron saints) and several seasonal festivals—carried into the Christian period.

Since the conversion to Christianity, Roman Catholicism, with its ecclesiastical seat at Armagh in Northern Ireland, has been the island’s principal religion. After the Reformation, Catholicism became closely associated with Irish nationalism and resistance to British rule. However, church support for nationalism—both then and now—has been ambivalent. After the devastating Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s, there was a remarkable surge in devotional support of the Catholic church, and over the next century the number of Irish priests, nuns, and missionaries grew dramatically.

Today nearly four-fifths of the republic’s population is Roman Catholic, with small numbers of other religious groups (including Church of Ireland Anglicans, Presbyterians, Methodists, Muslims, and Jews). There is no officially established church in Ireland, and the freedoms of conscience and religion are constitutionally guaranteed. Since the last decades of the 20th century, Ireland has seen a significant decline in the number of regular churchgoers. That decline corresponded with the heyday of the so-called Celtic Tiger economy—when, during the 1990s in particular, robust economic growth made the country significantly wealthier—and also with the revelations of child abuse by Catholic clergy that came to light in the first decade of the 21st century. The Roman Catholic Church nevertheless continues to play a prominent role in the country, including maintaining responsibility for most schools and many hospitals.

Cultural Life of Ireland

The cultural milieu of Ireland has been shaped by the dynamic interplay between the ancient Celtic traditions of the people and those imposed on them from outside, notably from Britain. This has produced a culture of rich, distinctive character in which the use of language—be it Irish or English—has always been the central element. Not surprisingly, Irish culture is best known through its literature, drama, and songs; above all, the Irish are renowned as masters of the art of conversation.

Use of the Irish language declined steadily during the 19th century and was nearly wiped out by the Great Famine of the 1840s and subsequent emigration, which particularly affected the Irish-speaking population in the western portion of the country—the area “beyond the pale” (i.e., beyond the English-speaking and English-controlled area around Dublin). From the mid-19th century, in the years following the famine, there was a resurgence in Irish language and traditional culture. This Gaelic revival led in turn to the Irish literary renaissance of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in which native expression was explored and renewed by a generation of writers and academics. It also produced a resurgence in traditional musical and dance forms. The cultural revivalism became an inspiration to the Irish nationalist struggle of the early decades of the 20th century. Partly because of government subsidies and programs, traditional cultural activities, especially the use of the Irish language and the revival of arts and crafts, have increased.

Daily life and social customs

Ireland has several distinct regional cultures rather than a single national one; moreover, the daily lives of city dwellers are in some ways much different from those living in the countryside. For example, whereas Dublin is one of Europe’s most cosmopolitan cities, the Blasket Islands of Dingle Bay, off Ireland’s southwestern coast, seem almost a throwback to earlier centuries. Wherever they live, the Irish maintain a vibrant and lively folk culture. Thousands participate in the country’s numerous amateur musical, dance, and storytelling events. A great many also engage in a variety of craft-based industries, producing items such as glass, ceramics, ironwork, wood-turning, linens, embroidery, and knitwear, served by the Crafts Council of Ireland (based in Kilkenny) and an annual trade fair in Dublin. Irish fashion has advanced beyond the still-popular Aran sweater, with various designers establishing fashion trends that have broad appeal both nationally and internationally.

The Irish pub serves as a focal point for many small villages and urban neighbourhoods, a place where the great Irish passion for conversation, stories, and jokes can be indulged. Pub attendance declined somewhat in the early 21st century after the imposition of a smoking ban, the restriction of hours when families could take children to eat at pubs, and the enactment of more-stringent drunk-driving laws. Still, Ireland remains home to some of the world’s finest beers, whiskeys, and other spirits, which accompany the lively music and socializing that seem to come naturally to the Irish and those who visit. Traditional Irish music—using locally made instruments such as the fiddle, the tin whistle, and the uilleann pipes (Irish bagpipes)—is performed at many pubs, and traditional songs are often sung there in Irish, at times accompanied by the Celtic harp (an emblem of Ireland). The céilí, a traditional musical gathering, is an enduring expression of Irish social life that has counterparts in other Celtic cultures. Such gatherings, as well as hiring fairs, cattle shows, and other festivals, usually feature locally produced ales and whiskeys and traditional foods such as soda bread, corned beef, and colcannon (a stew of potatoes and cabbage).

The Wexford Opera Festival, held annually in the fall, draws a large international audience. Of particular importance is St. Patrick’s Day (March 17), honouring the country’s patron saint. Whereas overseas the holiday has become a boisterous, largely secular celebration of all things Irish, in Ireland it is a religious occasion often observed by saying prayers for peace, especially in neighbouring Northern Ireland. Nevertheless, some of the practices celebrated abroad have been adopted locally in the interest of tourism.

The arts

The earliest known literature in the Old Irish language takes several forms. Many manuscripts, such as the Milan and Turin glosses on the Bible (so named for the libraries where they are housed), are religious in nature; others are secular and include lyric poems, fragments of epic verse, and riddles. Little of this literature is read today except by scholars of the Irish language and of comparative historical linguistics. Instead, the stream of Irish literature that has enriched world culture has been almost entirely written in English. The sheer volume of work attributed to Irish writers is remarkable, considering the country’s small size and, until relatively recently, its only partially literate populace.

A flowering of Irish literary works especially occurred with the standardization of Irish in the mid-20th century. After World War II a new wave of poets, novelists, and dramatists produced a significant literature in modern Irish, among them Máirtín Ó Cadhain, Máirtín Ó Direáin, and Máire Mhac an tSaoi. Beginning in the 1970s, another generation of writers made important contributions in Irish, notably Micheal O’Siadhail, Gabriel Rosenstock, Michael Hartnett, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Áine Ní Ghlinn, and Cathal Ó Searcaigh.

Many modes of thought and expression characteristic of Irish-language formulations were gradually absorbed into the English spoken in Ireland. The remarkable contribution that Anglo-Irish literature and drama have made to the Western world may in part be ascribed to this linguistic cross-fertilization. It is also noteworthy that so small a country should produce so much creative literary genius. The great Anglo-Irish satirist Jonathan Swift, dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, drew upon his experience of life in Ireland for his writing. The list of influential Irish prose writers and poets who both benefited from and contributed to the interplay between the different strands of the Anglo-Irish tradition is long. Among them are two of Ireland’s four winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature, poets William Butler Yeats (1923) and Seamus Heaney (1995). Others with an international reputation include prose writers George Moore, Elizabeth Bowen, Flann O’Brien, Edna O’Brien, William Trevor, John McGahern, Roddy Doyle, John Banville, Jennifer Johnston, and especially James Joyce; and poets John Montague (American-born), Eavan Boland, Brendan Kennelly, Paul Durcan, and Paula Meehan. The Irish Writers’ Centre and Poetry Ireland actively promote contemporary literature in prose and verse.

Discover Dublin

Dublin’s Fair City is very much “alive alive-o”, and even with restrictions in place, the sights are still as vibrant and interesting as the inhabitants themselves.

Here, we present a small sampling of what Dublin is made of; but more than anything, it’s made of Dubliners, reflecting their resilient spirit, irrepressible sense of humour, pride in their home, and passion for discovery. While some aspects of life in our unique city may be temporarily paused, this is the perfect opportunity for locals to seek out spots they may have missed; it’s time to reclaim and renew your acquaintance with what makes it not just unbeatable… but truly unstoppable.