Portugal - Europe's West Coast

Portugal is a southern European country on the Iberian Peninsula, bordering Spain. Its location on the Atlantic Ocean has influenced many aspects of its culture: salt cod and grilled sardines are national dishes, the Algarve’s beaches are a major destination and much of the nation’s architecture dates to the 1500s–1800s, when Portugal had a powerful maritime empire.

With its mild climate, 3000 hours of sunshine per year and 850 kms of splendid beaches bathed by the Atlantic Ocean, Portugal is the perfect holiday destination all year round.

This is a country that has the oldest borders in Europe, with an exceptional range of different landscapes just a short distance away, lots of leisure activities and a unique cultural heritage, where tradition and modernity blend together in perfect harmony. Its superb cuisine, fine wines and hospitable people make this a tourist paradise of the highest quality.

Situated in the extreme south-west of Europe, just a few hours from any of the other European capitals, Portugal attracts visitors from all over the world.

Come and discover the charms of this country too.

History of Portugal

Pre-Roman, Roman, Germanic, and Muslim periods

The earliest human remains found in Portugal are Neanderthal-type bones from Furninhas. A distinct culture first emerged in the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) middens of the lower Tagus valley, dated about 5500 BCE. Neolithic (New Stone Age) cultures entered from Andalusia, leaving behind varied types of beehive huts and passage graves. Agriculture, pottery, and the working of soft metals followed by the same route. In the 1st millennium BCE, Celtic peoples entered the peninsula via the Pyrenees, and many groups were projected westward by natural pressure. Phoenician and later Carthaginian influence reached southern Portugal in the same period. By 500 BCE, Iron Age cultures predominated in the north. Celtic hilltop settlements (castros) retained their vitality after the Roman conquest.

After the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE), Rome dominated the eastern and southern seaboards of the Iberian Peninsula, and Celtic peoples who had partially absorbed the indigenous population occupied the west. A Celtic federation, the Lusitani, resisted Roman penetration under the brilliant leadership of Viriathus; however, after Viriathus was assassinated about 140 BCE, Decius Junius Brutus led a Roman force northward through central Portugal, crossed the Douro River, and subdued the Gallaeci. Julius Caesar governed the territory for a time. In 25 BCE Caesar Augustus founded Augusta Emerita (Mérida) as the capital of Lusitania, which incorporated present-day central Portugal. Gallaecia (Galicia), to the north of the Douro, became a separate province under the Antonines. In Roman times the present-day districts of Beja and Évora formed a wheat belt. The valley of the Tagus was famous for its horses and farms, and there were important mines in the Alentejo. Notable Roman remains include the Temple of Diana at Évora and the site of Conimbriga (Condeixa). Christianity reached Lusitania in the 3rd century and Galicia in the 4th.

After 406 CE, foreign invaders forced their way into Gaul and crossed the Pyrenees. A Germanic tribe, the Suebi, settled in southern Galicia, and their rulers resided at or near Bracara Augusta (Braga) and Portucale. The Suebi annexed Lusitania and for a time overran the rest of the peninsula, but the Visigoths subdued them and extinguished their monarchy in 469. There are no records until about 550, when the Suebic monarchy had been restored and was reconverted to Catholicism by St. Martin of Braga. When Muslim forces invaded in 711, the only serious Gothic resistance was made at Mérida; upon its fall the northwest submitted. Berber troops were placed in central Portugal and Galicia. When ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I set up the Umayyad monarchy at Córdoba in 756, there was some resistance in the west; indeed, Lisbon was independent for a few years in the early 9th century. The restoration of the Christian sees of Galicia, the discovery of the supposed tomb of St. James, and the erection of his shrine at Santiago de Compostela (Santiago) were followed by the organization of the frontier territory of Portucale in 868 by Vimara Peres; Coimbra was annexed by the Christians but later was lost again.

The county and kingdom of Portugal to 1383

By the 10th century the county of Portugal (north of the Douro) was held by Mumadona Dias and her husband Hermenegildo Gonçalves and their descendants, one of whom was tutor and father-in-law to the Leonese ruler Alfonso V. However, when this dynasty was overthrown by the Navarrese-Castilian house of Sancho III Garcés (Sancho the Great), the western county lost its autonomy. Sancho’s son Ferdinand I of Castile reconquered Coimbra in 1064 but entrusted it to a Mozarabic governor. When the African Almoravids annexed Muslim Spain, Alfonso VI, who ruled Castile and León (1072–1109), provided for the defense of the west by calling on Henry, brother of Duke Eudes (Odo) of Burgundy, whom he married to his illegitimate daughter Teresa and made count of Portugal. Thus, from 1095 Henry and Teresa (who used the title of queen) ruled Portugal and Coimbra. Upon Alfonso VI’s death, his realms passed to his daughter Urraca, who was queen from 1109 to 1126, and her little son Alfonso (who became Alfonso VII upon Urraca’s death). Henry of Portugal sought power but had achieved little when he died in 1112, leaving Teresa with an infant son, Afonso Henriques (later Afonso I). Teresa’s intrigues with her Galician favourite, Fernando Peres of Trava, lost her the support of the Portuguese barons, and in 1128 followers of Afonso Henriques defeated her and drove her into exile.

Afonso Henriques became count of Portugal, and, although he was at first obliged to submit to Alfonso VII, his cousin, Afonso began to use the title of king, according to tradition following on his victory over the Muslims at Ourique on July 25, 1139 (though this may be more legend than history). In 1143 Alfonso VII accepted his cousin’s autonomy, but the title of king was formally conceded only in 1179, when Afonso Henriques placed Portugal under the direct protection of the Holy See, promising an annual tribute. Afonso had captured Santarém (March 1147) and Lisbon (October 1147), the latter with the aid of English, French, German, and Flemish Crusaders bound for Palestine. An English priest, Gilbert of Hastings, became the first bishop of the restored see of Lisbon.

The county and kingdom of Portugal to 1383

By the 10th century the county of Portugal (north of the Douro) was held by Mumadona Dias and her husband Hermenegildo Gonçalves and their descendants, one of whom was tutor and father-in-law to the Leonese ruler Alfonso V. However, when this dynasty was overthrown by the Navarrese-Castilian house of Sancho III Garcés (Sancho the Great), the western county lost its autonomy. Sancho’s son Ferdinand I of Castile reconquered Coimbra in 1064 but entrusted it to a Mozarabic governor. When the African Almoravids annexed Muslim Spain, Alfonso VI, who ruled Castile and León (1072–1109), provided for the defense of the west by calling on Henry, brother of Duke Eudes (Odo) of Burgundy, whom he married to his illegitimate daughter Teresa and made count of Portugal. Thus, from 1095 Henry and Teresa (who used the title of queen) ruled Portugal and Coimbra. Upon Alfonso VI’s death, his realms passed to his daughter Urraca, who was queen from 1109 to 1126, and her little son Alfonso (who became Alfonso VII upon Urraca’s death). Henry of Portugal sought power but had achieved little when he died in 1112, leaving Teresa with an infant son, Afonso Henriques (later Afonso I). Teresa’s intrigues with her Galician favourite, Fernando Peres of Trava, lost her the support of the Portuguese barons, and in 1128 followers of Afonso Henriques defeated her and drove her into exile.

Afonso Henriques became count of Portugal, and, although he was at first obliged to submit to Alfonso VII, his cousin, Afonso began to use the title of king, according to tradition following on his victory over the Muslims at Ourique on July 25, 1139 (though this may be more legend than history). In 1143 Alfonso VII accepted his cousin’s autonomy, but the title of king was formally conceded only in 1179, when Afonso Henriques placed Portugal under the direct protection of the Holy See, promising an annual tribute. Afonso had captured Santarém (March 1147) and Lisbon (October 1147), the latter with the aid of English, French, German, and Flemish Crusaders bound for Palestine. An English priest, Gilbert of Hastings, became the first bishop of the restored see of Lisbon.

Although Afonso II was an unwarlike king, his followers were beside the Castilians at the great Christian victory in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 and, again assisted by Crusaders, recovered Alcácer do Sal in 1217. Meanwhile, Afonso repudiated the bequests of large estates made by his father to his brothers and accepted those to his sisters only after a war with León and in a form, settled by the pope, that recognized Afonso’s sovereignty. In the first year of his reign, Afonso called a meeting of the Cortes (parliament) at Coimbra, to which the nobility and prelates were summoned (representatives of the commoners were not to appear until 1254). Both estates obtained important concessions; in fact, the position of the church and the orders was now so strong that Afonso II and his successors were involved in recurrent conflicts with Rome. Afonso himself instituted (from 1220) inquirições, or royal commissions, to investigate the nature of holdings and to recover whatever had been illegally taken from the crown.

Little is known of the reign of his son Sancho II (1223–c. 1246), but the reconquest of the Alentejo was now completed, and much of the Algarve had also been retaken. When Sancho became king, he found the church in full ascendancy as a result of the agreement made before his father’s death. At all events, his younger brother Afonso, who had become count of Boulogne through his marriage (1238) to Matilde, daughter of Raynald I, Comte (count) de Dammartin, was granted a papal commission (1245) to take over the government, and Sancho was ordered to be deposed by papal bull. When Afonso reached Lisbon (late 1245 or early 1246), he received the support of the church and of the inhabitants of Lisbon and other towns. After a civil war lasting two years, Sancho II retired to Toledo, dying there in January 1248.

On his arrival the count of Boulogne had already declared himself king as Afonso III, and the death of Sancho without issue gave his usurpation the mantle of legality. He brought together the divided kingdom, completed the reconquest of the Algarve, transferred the capital from Coimbra to Lisbon, and, fortified by the support of the towns, summoned the Cortes at Leiria, where in 1254 commoners representing the municipalities made their first appearance. Afonso III’s conquest of the Algarve aroused the jealousy of Castile. Campaigns were fought in 1250 and 1252, and peace was made only by means of a marriage pact. Although still the husband of Matilde of Boulogne, Afonso married Beatriz, illegitimate daughter of Alfonso X of Castile, holding the disputed territory of the Algarve as a fief of Castile until the eldest son of the marriage should reach age seven, at which time the Algarve was to return to Portugal. This marriage led to a dispute with the Holy See, in which Afonso was placed under an interdict. Though beholden to Rome, Afonso refused to give way; in 1263 the bigamous marriage was legalized and his eldest son, Dinis, legitimized. Shortly afterward Afonso launched inquirições that deprived the church of much property. The prelates protested these actions of the royal commissions, and most of them subsequently left the country. Although Afonso was excommunicated and threatened with deposition, he continued to defy the church until shortly before his death early in 1279.

The achievements of Afonso’s reign—the completion of the Reconquista, the assertion of royal power before the church, and the incorporation of the commoners in the Cortes—indicate important institutional advances. Under his son Dinis (1279–1325), Portugal came into closer touch with western Europe. The chartering of fairs and the increased use of minted money bear witness to the growth of commerce, and the planting of pine forests to hold back the advancing sand dunes near Leiria illustrates Dinis’s interest in furthering shipbuilding and agriculture. Having already adopted various measures to stimulate foreign trade, Dinis in 1317 engaged a Genoese admiral, Emmanuele Pessagno, to build up his navy. He founded the University of Coimbra (at first in Lisbon) in 1290 and was both a poet and a patron of literature. Yet he was especially famed as the rei lavrador (farmer king) for his interest in the land.

Despite Dinis’s attachment to the arts of peace, Portugal was involved in strife several times during his reign. In 1297 the Treaty of Alcañices with Castile confirmed Portugal’s possession of the Algarve and provided for an alliance between Portugal and Castile. The mother of Dinis’s son, the future Afonso IV (1325–57), was Isabel, daughter of Peter III of Aragon. This remarkable woman, later canonized as St. Elizabeth of Portugal and popularly known as the Rainha Santa (the Holy Queen), successfully exercised her influence in pursuit of peace on several occasions.

Disputes with Castile

Afonso IV (the Brave) was also involved in various disputes with Castile. Isabel, who had retired to the convent of Santa Clara at Coimbra, continued to intervene in favour of peace. However, upon Isabel’s death in 1336 war broke out, and peace terms were not made until 1340, when Afonso, leading a Portuguese army, joined Alfonso XI of Castile in the great victory over the Muslims on the Salado River in Andalusia. Afonso’s son Peter was married (1336) to Constança (died 1345), daughter of the Castilian infante Juan Manuel. Soon after the marriage, however, Peter fell in love with her cousin Inês de Castro, with whom he had several children. Afonso was persuaded to allow the assassination of Inês in 1355, and one of the earliest acts of Peter I as king was to take vengeance on her murderers. During his short reign (1357–67), Peter devoted himself to the dispensation of justice; his judgments, which he executed himself, were severe and often violent, and his iron rule was tempered only by fits of reveling.

Ferdinand I (1367–83), Peter’s son by Constança, inherited a wealthy throne almost free of external entanglements, but the dispute between Peter, king of Castile and León, and Henry of Trastámara (later Henry II) over the Castilian throne was raging. On the murder of Peter in 1369, several Castilian towns offered Ferdinand their allegiance, which he was unwise enough to accept. Henry II duly invaded Portugal, and, by the Peace of Alcoutim (1371), Ferdinand was forced to renounce his claim and to promise to marry Henry’s daughter; however, he instead took a Portuguese wife, Leonor Teles, despite the fact that she was already married and against the wishes of the commoners of Lisbon. In 1372 Ferdinand made an alliance with the English through John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, who had married the elder daughter of Peter and claimed the Castilian throne. In 1372 Ferdinand provoked Henry II, who invaded Portugal and besieged Lisbon. Unable to resist, Ferdinand was forced to repudiate his alliance with John of Gaunt and to act as an ally of Castile, surrendering various castles and persons as hostages. It was only on the death of Henry in 1379 that Ferdinand dared to openly challenge Castile again. In 1380 the English connection was resumed, and in the following year John of Gaunt’s brother Edmund of Langley, earl of Cambridge (afterward Edmund of Langley, 1st duke of York), took a force to Portugal for the invasion of Castile and betrothed his son Edward to Ferdinand’s only legitimate child, Beatriz. In mid-campaign Ferdinand came to terms with the enemy (August 1382), agreeing to marry Beatriz to a Castilian prince. She did, in effect, become the wife of John I of Castile, and, when Ferdinand died prematurely decrepit, Leonor became regent and Castile claimed the Portuguese crown.

Leonor had long been the paramour of the Galician João Fernandes Andeiro, conde de Ourém, who had intrigued with both England and Castile and whose influence was much resented by Portuguese patriots. Opponents of Castile chose as their leader an illegitimate son of Peter I: John, master of Aviz, who killed Ourém (December 1383) and, being assured of the support of the populace of Lisbon, assumed the title of defender of the realm. Leonor fled first to Alenquer and then to Santarém, and the king of Castile came to her aid; soon, however, he relegated her to a Spanish convent. Lisbon was besieged for five months (1384), but an outbreak of plague forced the Castilians to retire.

The house of Aviz, 1383–1580

The legitimate male line of Henry of Burgundy ended at Ferdinand’s death, and, when the Cortes met at Coimbra in March–April 1385, John of Aviz was declared king (as John I) and became the founder of a new dynasty. This result was not unopposed, as many of the nobility and clergy still considered the queen of Castile the rightful heiress. However, popular feeling was strong, and John I had valuable and trusted allies in Nuno Álvares Pereira, “the Holy Constable,” his military champion, and in João das Regras, his chancellor and jurist.

Independence assured

A number of towns and castles still held out for Castile when in August 1385 John I of Castile and a considerable army made their appearance in central Portugal. Although much outnumbered, the Portuguese won the great Battle of Aljubarrota (August 14, 1385), in which the Castilian chivalry was dispersed and John of Castile himself barely escaped. The victory assured John I of his kingdom and made him a desirable ally. A small force of English archers had been present at Aljubarrota in support of the Portuguese. The Treaty of Windsor, concluded on May 9, 1386, raised the Anglo-Portuguese connection to the status of a firm, binding, and permanent alliance between the two crowns. John of Gaunt duly went to the Iberian Peninsula in July 1386 and attempted an invasion of Castile in conjunction with John I. The invasion was not successful, but in 1387 the Portuguese king married John of Gaunt’s daughter Philippa of Lancaster, who introduced various English practices into Portugal. The truce arranged with Castile in 1387 was prolonged at intervals until peace was finally concluded in 1411.

The victory of John I may be regarded as a triumph of the national spirit over the feudal attachment to established order. Because much of the older nobility sided with Castile, John rewarded his followers at their expense and the crown’s. Meanwhile, commerce prospered, and the marriage of John’s daughter Isabella to Philip III (the Good) of Burgundy was to be followed by the growth of close trading relations between Portugal and Philip’s county of Flanders. With the conclusion of peace with Castile, John found an outlet for the activities of his frontiersmen and of his own sons in the conquest of Ceuta (1415), from which the great age of Portuguese expansion may be dated.

In 1437, during the short reign of John’s eldest son, Edward (Duarte; 1433–38), an unsuccessful attempt to conquer Tangier was made by John’s third son, Prince Henry the Navigator, and his younger brother Ferdinand (who was captured by the Moors and died, still unransomed, in 1443). Edward’s son Afonso V (1438–81) was still a child when Edward died, and Edward’s brother Pedro, duke of Coimbra (Dom Pedro), had himself made regent (1440) instead of the widow, Leonor of Aragon. However, Pedro’s own regency was later challenged by the powerful Bragança family, descended from Afonso, illegitimate son of John of Aviz, and Beatriz, daughter of Nuno Álvares Pereira. This family continued to set the young king against his uncle, who was forced to resign the regency, driven to take up arms, and killed at Alfarrobeira (May 1449). Afonso proved unable to resist the demands of the Braganças, who now became the wealthiest family in Portugal. Having married Joan, daughter of Henry IV of Castile, Afonso laid claim to the Castilian throne and became involved in a lengthy struggle with Ferdinand and Isabella in the region of Zamora and Toro, where he was defeated in 1476. He then sailed to France in a failed attempt to enlist the support of Louis XI, and on his return he concluded with Castile the Treaty of Alcáçovas (1479), abandoning the claims of his wife. Afonso never recovered from his reverse, and during his last years his son John administered the kingdom.

Consolidation of the monarchy

John II (1481–95) was as cautious, firm, and jealous of royal power as his father had been openhanded and negligent. At his reign’s first Cortes, John exacted a detailed oath of homage that displeased his greatest vassals. A suspicion of conspiracy enabled him to arrest Fernando II, duke of Bragança, and many of his followers; the duke was sentenced to death and executed at Évora in 1484. As well as attacking the power of the nobility, John lessened the effects of the unfavourable treaty with Castile. Calculating and resolute, he later received the epithet “the Perfect Prince.”

Predeceased by his legitimate son, John II was succeeded by his cousin the duke of Beja, as Manuel I (1495–1521), known as “the Fortunate.” Manuel, who assumed the title of “Lord of the Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce of India, Ethiopia, Arabia, and Persia,” inherited, because of the work of John II, a firmly established autocratic monarchy and a rapidly expanding overseas empire. Drawn toward Spain by the common need to defend their overseas interests as defined by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), Manuel nourished the hope that the whole peninsula could be united under the house of Aviz; to that end he married Isabella, eldest daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella. However, she died in 1498 while giving birth to a son, Miguel da Paz. This child, recognized as heir to Portugal, Castile, and Aragon, died in infancy. Manuel then married Isabella’s sister Maria (died 1517) and eventually Eleanor, sister of the emperor Charles V.

As a condition of his marriage to Isabella, Manuel was required to “purify” Portugal of Jews. After Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, John II had admitted many Jewish refugees; he had taxed the Jews heavily but was also to supply ships for them to leave Portugal. This was not done, however, and Manuel now ordered all Jews to leave within 10 months, by October 1497. On their assembly in Lisbon, every effort was made to secure their conversion by promises or by force. Some who resisted were allowed to go, but the rest were “converted” under promise that no inquiry would be made into their beliefs for 20 years. As “Christians,” they could not be forced to emigrate, and, indeed, they were prohibited from leaving Portugal. In April 1506 a large number of these “new Christians,” or Marranos, were massacred in Lisbon during a riot, but Manuel afterward protected the Marranos and allowed many to emigrate to Holland, where their experience with Portuguese trade was put at the service of the Dutch.

If Manuel failed to realize his dream of ruling Spain, his son John III (1521–57) lacked the power to resist Castilian influence. A pious, retiring man, he was ruled by his wife, Catherine, sister of Emperor Charles V, and encouraged the installation of the Inquisition (1536); the first auto-da-fé (“act of faith,” a public condemnation or punishment of so-called heretics during the Inquisition) was held in 1540. The Society of Jesus (the Jesuits), established in 1540, soon controlled education in Portugal. In 1529 the settlement by the Treaty of Zaragoza (Saragossa) of a dispute over the possession of the Moluccas (an island group part of present-day Indonesia) removed an obstacle to Portuguese-Spanish understanding, and the line dividing Portuguese and Spanish interests in the New World (established by the Treaty of Tordesillas) was matched by a similar line in the Pacific. Meanwhile, this dual theoretical division of new lands between the Portuguese and Spanish and the Reformation had come between Portugal and its English ally.

John III was succeeded by his grandson Sebastian (1557–78), then only three years old. As a child Sebastian became obsessed with the idea of a Crusade against Morocco. Fanatically religious, he had no doubts of his own powers and listened only to flatterers. He visited Ceuta and Tangier in 1574 and began in 1576 to prepare a large expedition against Larache; his forces departed in June 1578 and on August 4 were utterly destroyed by the Moors in the Battle of the Three Kings near Alcazarquivir (Ksar el-Kebir). Sebastian and some 8,000 of his forces were killed, some 15,000 were captured, and only a handful escaped.

Sebastian was succeeded by his great-uncle, Cardinal Henry (1578–80), a brother of John III. His age and celibacy made it certain that the Portuguese throne would soon pass from the direct line of Aviz. Philip II of Spain, nephew of John III and husband (by his first marriage) of John’s daughter Maria, had already made his preparations, and, when the cardinal-king died on January 31, 1580, Philip summoned the authorities to obey him. An army under the great duke of Alba entered Portugal in 1580; the resistance of António, prior of Crato (illegitimate son of John III’s brother Luís), acclaimed António I at Santarém, collapsed; and Philip II of Spain became Philip I of Portugal (1580–98).

Medieval social and economic development

Medieval Portugal comprised regions of considerable diversity. In the north the old aristocracy of Leonese descent owned large estates worked mainly by serfs. In the southern territory that had been reconquered from Muslim rule, there were many towns, often separated by districts almost barren and depopulated. Cistercian monks, who had reached Portugal by 1143, took the initiative in settling these areas; later kings such as Sancho I and Afonso III established concelhos (municipalities), granting them chartered privileges designed to attract settlers. Tax concessions were often given, and freedom was promised to serfs or to Christian captives after a year’s residence. In the south, however, the concelhos were burdened with defense duties. The cavaleiros-vilãos (villein knights) were obliged to horse and arm themselves; the peões, or less-substantial men, were required to serve as foot soldiers in defense of the country and perhaps also on a fossado (raid) into Muslim territory.

At court the king was advised by his curia regis (court or council), comprising the majordomus curiae, the head of the administration, the military chief or signifer, the dapifer curiae (steward of the household), the chancellor (an official whose origins in Portugal were Burgundian rather than Visigothic), and any members of the greater aristocracy, the ricos-homens, who might be at court. The ricos-homens also comprised the bishops and abbots and masters of the orders of knighthood; many held private civil or military authority. The lesser nobility were without such rights. Below them came various classes of free commoners, such as the cavaleiros-vilãos and the malados, men who had commended themselves to protectors. There were numerous serfs and slaves.

There had been several shifts in the social structure by the end of the medieval period. Many of the old aristocracy lost their position at the advent of the house of Aviz, and the new nobility, exemplified in the house of Bragança, was often of bureaucratic or ministerial origin. Representatives of the commoners, first attending the Cortes in 1254 on behalf of the concelhos, took an increasing part in politics. The Cortes were very frequently called during the reigns of John I, Edward, and Afonso V, but the avenues of power had become wider by the 16th century, and John III’s proposal (1525) to call them only every 10 years aroused no opposition. Although the trade guilds were slow in developing, they took some part in determining local taxation in the 13th century. Trade increased, Portuguese merchants having had connections with the Low Countries from the time of Afonso Henriques and with England from the early 13th century. The political crisis of 1385 was followed by inflation and debasements; thereafter there was no national gold currency until 1435, when West African sources began to be tapped.

People of Portugal

At court the king was advised by his curia regis (court or council), comprising the majordomus curiae, the head of the administration, the military chief or signifer, the dapifer curiae (steward of the household), the chancellor (an official whose origins in Portugal were Burgundian rather than Visigothic), and any members of the greater aristocracy, the ricos-homens, who might be at court. The ricos-homens also comprised the bishops and abbots and masters of the orders of knighthood; many held private civil or military authority. The lesser nobility were without such rights. Below them came various classes of free commoners, such as the cavaleiros-vilãos and the malados, men who had commended themselves to protectors. There were numerous serfs and slaves.

There had been several shifts in the social structure by the end of the medieval period. Many of the old aristocracy lost their position at the advent of the house of Aviz, and the new nobility, exemplified in the house of Bragança, was often of bureaucratic or ministerial origin. Representatives of the commoners, first attending the Cortes in 1254 on behalf of the concelhos, took an increasing part in politics. The Cortes were very frequently called during the reigns of John I, Edward, and Afonso V, but the avenues of power had become wider by the 16th century, and John III’s proposal (1525) to call them only every 10 years aroused no opposition. Although the trade guilds were slow in developing, they took some part in determining local taxation in the 13th century. Trade increased, Portuguese merchants having had connections with the Low Countries from the time of Afonso Henriques and with England from the early 13th century. The political crisis of 1385 was followed by inflation and debasements; thereafter there was no national gold currency until 1435, when West African sources began to be tapped.

More than nine-tenths of the country’s population are ethnic Portuguese, and there are also small numbers of Brazilians, Han Chinese, and people from Portugal’s former colonial possessions in Africa and Asia. Ethnic Marranos (descendants of Jews who converted to Christianity but who secretly continued to practice Judaism) constitute about 1 percent of the population, and the country’s Roma (Gypsy) population lives primarily in the Algarve. Language is an extremely common bond: Portuguese is the first language of nearly the entire population.

Religion

Some ninth-tenths of Portugal’s citizens are Roman Catholic. Regular attendance at mass, however, has declined in the cities and larger towns, particularly in the south. Less than 2 percent of the population is Protestant, with Anglicans and Methodists the oldest and largest denominations. In the late 20th century, fundamentalist and Evangelical churches grew in popularity, though the number of their adherents remained quite small. The Jewish population of Portugal is also tiny, as Jews were forced to convert or emigrate during the Inquisition in the late 15th century.

Language

From a Latin root, Portuguese is spoken by about 250 million people in every continent, and is the 5th most spoken language in the world and the 3rd, if we only consider the European languages.

The Portuguese-speaking countries are scattered all over the world. Portuguese is spoken in Africa (Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and São Tomé e Príncipe), in South America (Brazil) and in Asia, (East Timor, the youngest nation in the world), and it is also the official language in Macao Special Administrative Region of China.

In Portugal there are lots of people who are able to communicate in English, French and Spanish.

Cultural Life of Portugal

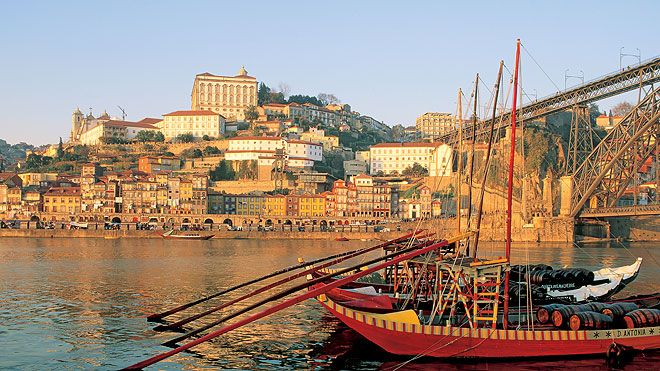

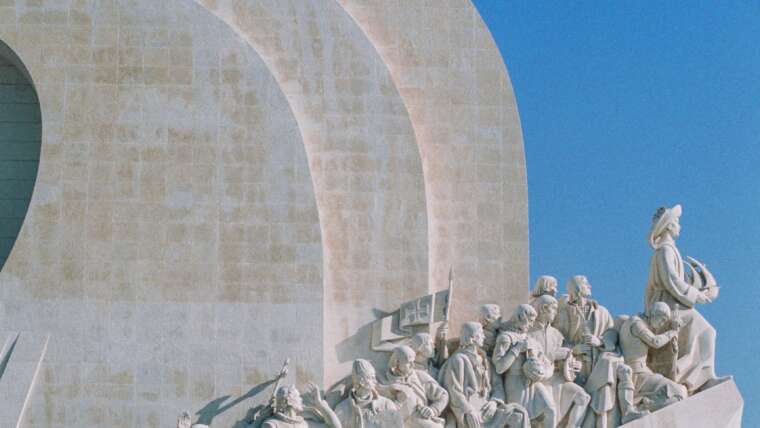

Portuguese culture is based on a past that dates from prehistoric times into the eras of Roman and Moorish invasion. All have left their traces in a rich legacy of archaeological remains, including prehistoric cave paintings at Escoural, the Roman township of Conimbriga, the Roman temple (known as the Temple of Diana) in Évora, and the typical Moorish architecture of such southern towns as Olhão and Tavira. Throughout the centuries Portugal’s arts have been enriched by foreign influences, including Flemish, French, and Italian. The voyages of the Portuguese explorers, such as Ferdinand Magellan, who was the first to circumnavigate the globe, and Vasco da Gama, who pioneered an eastern route to Asia around the Cape of Good Hope (the first European to sail around the cape was another Portuguese navigator, Bartolomeu Dias, in 1488), opened the country to Asian influences, and the revelation of Brazil’s wealth of gold and jewels fed the Baroque flame in decoration. There have been considerable efforts to conserve architecture and art across the country, especially religious artifacts, palaces, and the several distinctive styles of casas portuguesas, or modest homes. Preservation has led to the declaration of the city centres of Évora, Sintra, Porto, and, in the Azores, Angra do Heroísmo as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Daily life and social customs

Despite certain affinities with the neighbouring Spaniards, the Portuguese have their own distinctive way of life. The geographic variety of the country has evoked different responses, but there is less regionalism than in Spain. Moreover, lifestyles have altered radically as rural populations have declined and cities and their suburbs have expanded. Urban centres provide a range of entertainment, and fairs and markets are highlights of social gatherings. A long tradition of dancing and singing continues among the Portuguese. Nearly every village has its own terreiro, or dance floor, usually constructed of concrete, though in some places it is still made of beaten earth. Each region has its own style of dances and songs; most traditional songs are of a slower rhythm than those in Spain. Small accordions and gaitas, or bagpipes, are among a considerable range of instruments that accompany dances, and Portuguese guitars (and sometimes violas) accompany the fado, a song form that epitomizes saudade—the yearning, romantic aspect of the Portuguese character. Regional dances, which include the vira, chula, corridinho, tirana, and fandango, often reflect the courting and matrimonial traditions of the area. Much has been done to preserve these and other folk expressions as tourist attractions.

National dress is still seen in the northern Minho province at weddings and other festivals. Traditional garments such as the red and green stocking cap of the Alentejo cattleman still exist, and the samarra (a short jacket with a collar of fox fur) and cifões (the equestrian’s leather chaps) survive. Rustic plows and wooden carts drawn by oxen or mules are still used by small farmers (though in the perennial battle against forest fires, shepherds who guard their flocks in forest areas have been supplied with mobile phones). The wearing of black for protracted periods of mourning is common, especially in the villages.

Access to supermarkets has transformed eating habits in cities and urban areas. In the countryside the staple diet is one of fish, vegetables, and fruit. Although Portugal’s waters abound with fresh fish, the dried salted codfish known as bacalhau, now often imported, is considered the national dish. A seafood stew known as cataplana (for the hammered copper clamshell-style vessel in which it is cooked) is ubiquitous throughout the country. In many areas meat is seldom eaten, although the Alentejo region is known for its pork and Trás-os-Montes for cured meats. Cozido a portuguesa, a stew made with meats and vegetables, is a popular dish. Breads, cakes, and sweets—the last one a legacy of Moorish occupation—take a variety of forms, with many regional specialties. Portugal is well known for its wide variety of cheeses. Wine is the ubiquitous table beverage. In the north the wine of choice is often the red version of the so-called green wine, or vinho verde, usually preferred as a lightly sparkling white wine. Perhaps the most famous Portuguese export is the fortified wine called port, named after the town of Porto, where it has been bottled for centuries. Distinguished mainly for notable vintages, port is also enjoyed as ruby, tawny, and dry white varieties.

Portugal has a wide variety of regional fairs, many of which are combined with religious festivals. Religious customs in this Roman Catholic country still include, in the north, the burning of the yule log in the atrium of the village church at Christmas so that the poor may warm themselves. Twice annually (May and October) large numbers of the faithful make a pilgrimage to the shrine of Fátima, where three children reported that they had received messages from the Virgin Mary. All Saints’ Day festivals (November 1), especially in Lisbon and Porto, draw large crowds. Among the secular holidays are Liberty Day (April 25), which marks the Revolution of the Carnations of 1974 and is accompanied by parades and various cultural events; Portugal Day (June 10), which commemorates the death of 16th-century soldier-poet Luís de Camões; and Republic Day (October 5), which celebrates the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic in 1910.

The arts – Literature

The Portuguese language became synthesized in the 12th century, when a lyrical quality was outstanding in both poetry and prose. With Os Lusíadas (1572; The Lusiads), Camões first gave expression to the nation’s epic genius, and the 20th-century poet Fernando Pessoa, writing under numerous pseudonyms, introduced a Modernist European sensibility. Lyric poetry still flourishes. The tendency of fiction has been away from the romanticism of the 19th and early 20th centuries and toward realism. José Maria Eça de Queirós, whose works include Os Maias (1888; The Maias) and A cidade e as serras (1901; The City and the Mountains), was an outstanding realist novelist. In the first half of the 20th century, Aquilino Ribeiro was an exceptional regional novelist whose writings include Jardim das tormentas (1913; “Garden of Torments”) and O homem que matou o Diabo (1930; “The Man Who Killed the Devil”), while José Maria Ferreira de Castro was a notable realist and author of A selva (1930; The Jungle) and Os emigrantes (1928; “The Emigrants”). The novelist, essayist, and poet Vitorino Nemésio received acclaim for his novel Mau tempo no canal (1944; “Bad Weather in the Channel”; Eng. trans. Stormy Isles: An Azorean Tale).

Censorship under the Salazar regime considerably stifled meaningful literary production. With the revolution and the end of the dictatorship in 1974, literature flourished; among the notable figures of the postrevolutionary period were Neorealist poet and writer Fernando Namora (1919–89), poet and diarist Miguel Torga (1907–95)—both country doctors—and novelist Vergílio Ferreira (1916–96). Eduardo Lourenço was a leading essayist, and younger writers, such as Margarida Rebelo Pinto, gained popularity. Admired novelists in the late 20th and early 21st centuries included Almeida Faria, José Cardoso Pires, António Lobo Antunes, and José Saramago, the last of whom won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998. Among Saramago’s many works are Memorial do convento (1982; “Memoirs of the Convent”; Eng. trans. Baltasar and Blimunda); O ano da morte de Ricardo Reis (1984; The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis), a tribute to Fernando Pessoa; and O homem duplicado (2002; The Double). For further discussion, see Portuguese literature.

Architecture

Portugal boasts several scores of medieval castles, as well as the ruins of several villas and forts from the period of Roman occupation. Romanesque and Gothic influences have given Portugal some of its greatest cathedrals, and in the late 16th century a national style—Arte Manuelina—was synthesized by adapting several forms into a luxuriantly ornamented whole. Outstanding examples of Portuguese architecture include the ornate Manueline-style Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon; the Sé (cathedral) of Lisbon, in the facade of which the remains of Roman construction may still be seen; the Palace of Justice in Lisbon, a fine, soaring example of austere modern architecture; the castle and church of the Convent of Christ in Tomar; the late Portuguese Gothic abbey of Santa Maria da Vitória in Batalha; the granite Tower of the Clerics in Porto; and Braga’s Romanesque cathedral. Lisbon’s Baixa neighbourhood, in Pombaline style (named for Sebastião de Carvalho, marquês de Pombal, who rebuilt Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake), remains admirable today. As modern cities have expanded, there has been a revival of interest in traditional domestic and folk architecture, as is found in the hand-hewn stones of the Beiras, the low farms of the Alentejo, and the cottage chimneys in the Algarve.

Modern architecture has aroused considerable controversy. Some buildings with stark lines include the National Archives of Torre do Tombo, the Belém Cultural Centre, the grandiose Caixa Geral bank building, and the Expo ’98 site in the Parque das Nações, which includes an oceanarium and a railroad station. Some contemporary architects have successfully blended classical Portuguese styles with modern functions; among these are Fernando Távora, Nuno Teotónio Pereira, and Álvaro Siza Vieira, who was responsible for the successful reshaping of Lisbon’s Chiado area, a historic section of the city that suffered extensive fire damage in 1988.

Health and Well-being in Portugal

There’s nothing like an old recipe using ingredients offered by nature to take care of your health and to escape routine: fine weather, sunshine, clean air, clear waters, and plants and algae with therapeutic properties. You can depend on it. It may be at a thermal resort or a spa, by the sea or in the mountains.

There are different health and well-being programmes suitable for everyone. These relaxing moments, indispensable for restoring balance, can be undertaken in different ways.

At a thermal spa, using traditional techniques, enjoying the therapeutic properties and mineral richness of the waters; taking advantage of the extensive coastline and the Atlantic waters for thalassotherapy; or through relaxation sessions based on the regenerating effects of wine, chocolate or hot stones which you will find at spas and resorts as a complement to a holiday taken in style.

With opportunities all over the country, Portugal offers true havens to shake off the “diseases of modern life” and find peace and inner serenity and restore your energy.