Welcome to Wallis & Futuna Islands

Located over 16,000 kilometres from France, Wallis & Futuna are islands of immense natural beauty, far from the beaten track and still (mostly) undiscovered by tourists. According to official figures, around a hundred tourists visit Wallis & Futuna every year… And boats docking each year can be counted on the fingers of one hand! The situation is very different to that of other Pacific Ocean islands where several cruise ships stop off daily so passengers can spend a few hours visiting a city or site. Wallis & Futuna are islands out of time with a fascinating, traditional Polynesian culture still vibrantly alive today. A secluded paradise of smiling, hospitable islanders adorned with flower garlands.

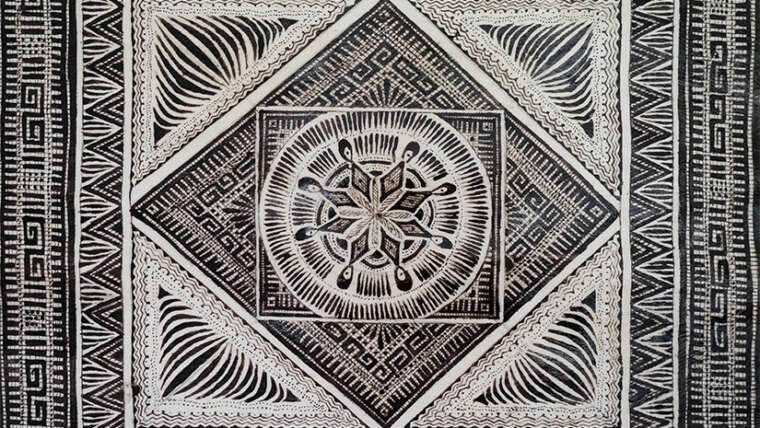

With their complex history (links with Tonga and Samoa, conversion by Catholic missionaries, links with France, occupation by US army forces, assimilation into the French Republic), Wallisians and Futunans boast a rich cultural heritage they are delighted to share with visitors.

Opulent Routes Presents Unparalleled Expeditions to Wallis and Futuna Islands

Nestled in the heart of the South Pacific, the Wallis and Futuna Islands await your exploration with Opulent Routes. Experience the untouched beauty and rich cultural heritage of this Polynesian paradise. Our tailored journeys to the Wallis and Futuna Islands unveil a realm of pristine beaches, turquoise lagoons, and captivating traditions. Delve into the essence of this remote archipelago with personalized itineraries that fuse luxury with authentic encounters. From immersing in local village life to discovering the islands’ untouched landscapes, let Opulent Routes be your guide to an extraordinary expedition through the captivating Wallis and Futuna Islands.

History of Wallis and Futuna Islands

The earliest inhabitants in Wallis and Futuna were people of the Lapita culture, who had reached the islands by at least 800 BCE. Archaeological evidence indicates that the people engaged in agriculture and fishing. Later waves of other Polynesian sailors reached the islands about 1400 CE: Samoans settled on Futuna, and Tongans on Uvea.

The three kingdoms of Uvea, Alo, and Sigave were in place when the islands of Wallis and Futuna were first encountered by Europeans in the 17th century. The Dutch explorers Jakob Le Maire and Willem Schouten sighted Futuna in 1616 during the early voyages of exploration in the Pacific. A lapse of 151 years occurred before Capt. Samuel Wallis encountered Uvea in 1767. There was another lapse of more than 50 years before the whaling industry reached the area in the 1820s, and Europeans began to make regular calls at both islands.

French Marist priests arrived as missionaries in the 1830s. They achieved considerable success within a decade and have remained an important force in the politics of the island group. Protestants never mounted a serious challenge, and the inhabitants of the islands were spared the religious conflicts that were common elsewhere in the Pacific.

As early as the 1840s, the islanders petitioned for French protection, but France was slow to respond; the Wallis Islands became a French protectorate in 1887, and Futuna did so in the following year. Over the next five decades, the French administration became well-entrenched and ruled the colony with a relatively firm hand.

In 1942, during World War II, the Allies based 6,000 troops on Uvea, and within a short time they built a system of roads, two landing strips, and anchoring facilities in the lagoon. These developments still form the basis of the island’s infrastructure.

In 1959 the islanders elected to become an overseas territory of France. Historically, the people of Wallis and Futuna have demonstrated conservatism, opposing proposals for a change in their dependent status.

In 1998 a typhoon (tropical cyclone) destroyed most of the cultivated crops on Uvea, including the island’s banana plantations; recovery was aided by a grant from France. The 1998 Nouméa Accord, which increased New Caledonia’s autonomy from France, led to discussions regarding the future status of Wallis and Futuna’s large community of expatriates in New Caledonia; the accord had given New Caledonia the power to control immigration from Wallis and Futuna in exchange for providing economic aid. In 2003 the two governments concluded a bilateral agreement that redefined their relations under the Nouméa Accord, including provisions for regular discussions regarding issues affecting the expatriates.

There was instability in the three kingdoms in the early 21st century. The king of Sigave was deposed by members of his clan in 2003 and was not succeeded until five months later. Several years later the other two kingdoms were, for a time, simultaneously leaderless: the king of Wallis, Tomasi Kulimoetoke, died in 2007 after a 48-year reign, and the throne remained empty until July 2008; and in February 2008 the king of Alo, after having reigned only five years, was deposed by the kingdom’s chiefly clans amid criticism of his leadership style.

Conflicts over the islands’ leadership continued. The king of Wallis was removed in 2014, and the throne remained vacant for two years. In April 2016 conflict arose among the royal families regarding the choice of a new king, Tominiko Halagahu, who had been selected by chiefs of Wallis. Rival members, who believed the choice should have been theirs, installed Patalione Kanimoa two days after the first king’s coronation, and two monarchs ruled in opposition while a solution to the situation was sought.

People of Wallis and Futuna Islands

The indigenous people are Polynesians, but there are significant differences between the languages and peoples of Uvea and Futuna islands. It appears that Uvea was settled by at least 800 BCE, and the people were subsequently conquered by Tongans. As a consequence, cultural, historical, and linguistic ties link Uvea and Tonga. In contrast, local folklore suggests that Futunans had their origins in Samoa; their language is related to that of Samoa, and the Futunans share many cultural traits with Samoa. Both Wallisian (Uvean) and Futunan are Polynesian languages and, along with French, are official languages. While the people of the islands have long been governed by a French administration and the vast majority profess the Roman Catholic faith, they do not share a common identity. Futuna is reluctantly tied to Uvea, and its people have expressed a desire to have separate territorial status.

Villages are dispersed on the islands, mainly on the coast. There are no real urban areas. About two-thirds of the population lives on Uvea. The Uvean and Futunan population in New Caledonia is larger than that of the home islands. The majority of the expatriates in New Caledonia are Uveans. The exodus resulted from the pull of greater opportunities for employment abroad and the push of limited prospects and growing population pressures at home. Because of the remittances they contribute to the economy, the expatriates are an asset as long as they remain abroad, but they would place an intolerable burden on local resources if they were to return home.

The number of French expatriates in Wallis and Futuna has always been small. Of the total resident population in the islands, only a small number are of European descent.

Economy of Wallis and Futuna Islands

About four-fifths of the population of Wallis and Futuna engages in subsistence farming, growing yams, taros, bananas, and other food crops. Some livestock is raised (mostly pigs). The notion of selling produce from the land is contrary to traditional custom, wherein items are bartered and not sold. Similarly, fish are caught mostly to satisfy the immediate needs of family, near kin, and neighbours. Most fish are taken in sheltered areas within the fringing reef, and little fishing is done in the open sea.

Wallis and Futuna is truly resource-poor, and very little revenue is earned from exports. Revenues come from French government subsidies, licensing of fishing rights to Japanese and South Korean companies, import taxes, and remittances from expatriate workers in New Caledonia. Exports include small amounts of breadfruit, yams, and taros, along with trochus shells. Vietnam, New Caledonia, Italy, and Japan are the major recipients. Imports, which come mainly from France and Australia, include food products, electrical machinery, road vehicles, and building and public works supplies.

Uvea is more developed than Futuna. The French administration is located on Uvea, and that island has the better infrastructure. Its roads and public services are superior, and most households have running water and electricity. The government is the island’s largest single employer. In contrast, Futuna is somewhat isolated; there is only a partially surfaced road circling the island; and administrative positions are scarce. Wallis and Futuna attracts a limited amount of tourism.

There is an international airport at Hihifo, northern Uvea, that is linked to French Polynesia and New Caledonia. Flights operate between Uvea and Futuna islands. A cargo vessel travels between the islands and Nouméa, New Caledonia, about a dozen times a year.

Discover Wallis & Futuna Islands

Wallis is blessed with one the world’s loveliest lagoons whose pristine beauty remains untouched by pressure from tourism. The lagoon is dotted with 13 fairytale islets, all completely uninhabited. It takes barely ten minutes to reach a world of sublime, secluded beaches and shimmering azure waters, where you can snorkel in an underwater wonderland.

This is a watersports paradise. Wallis is famed as one of world’s top kitesurfing spots, with other attractions including sea kayaking, SUP boarding, scuba diving, va’a outrigger canoes and, of course, every possible kind of fishing! Futuna is also a dream playground for all watersports, and a spot beloved by surfing fans.